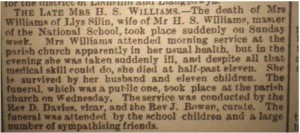

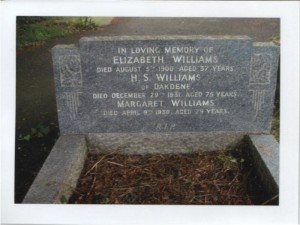

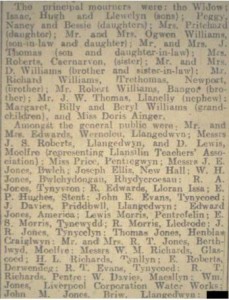

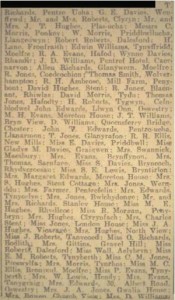

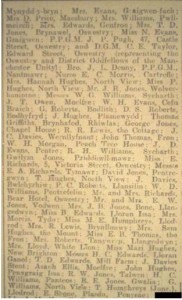

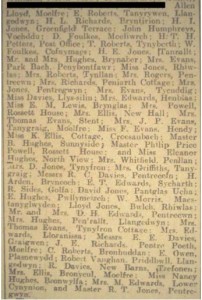

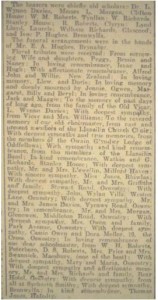

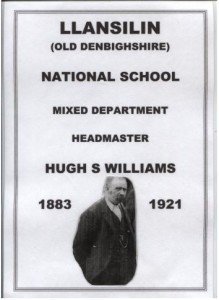

In every community there are one or two people who stand out from the crowd. Men and women who do something remarkable or charitable to improve the lives of those about them, and because of it are loved, respected and remembered. Hugh Solomon Williams was such a man. For forty two years, spanning the turn of the twentieth century he was the Head Master of the Church of England school in Llansilin, a farming village a few miles west of Oswestry. He attended to the education of the local children with huge enthusiasm and care but that wasn’t his only role in the village. Over the years he took on many other duties, including setting up choirs and brass bands, registrar of births, marriages and death, official at the Sheep Dog Trials and the Horticultural and Cattle Show, and more, too numerous to mention. He was born in 1858 in Llanrug, a village near Caernarvon, the eldest of the six children of Richard and Ellen Williams. Richard was a carrier in the Dinorwic slate quarry, and at the age of fourteen or fifteen, Hugh left school and joined his father, to work in that hard and dangerous industry. He’d been an industrious pupil at school and despite working at the quarry, he never lost his love of learning, reading books provided by the penny library and struggling to better his understanding of them. This love of learning was encouraged by the local chapel, where the minister, like many others of the cloth, in Wales, used education to better the lives of their flock. So when one day in 1880 an accident changed Hugh’s life, he had something to fall back on. In an interview with the Border Counties Advertiser in 1931 he recalled that day fifty years previously. ‘Going home one day I met with an accident when two cartloads of black powder were being brought along the road from Cwnglo to Llanberis and in going down an incline the powder exploded and parts of the men, horse and carts were scattered for a long distance. I was struck in the leg by a piece of the debris.’ This resulted in him being bedridden for some time and subsequently he walked with a pronounced limp. But he used his time in bed to read and study and by the time he was up and ready for work he determined that the quarry wasn’t for him and instead found himself a position as an elementary school teacher. He started at the village school in Llanrug honing his skills until 1883 when he moved to Llansilin bringing with him his new wife, Elisabeth Thomas. We’re not told how they met, Elisabeth came from Ystrad-ffin in Carmarthenshire and before her marriage she like her older sister, Margaret, had also been elementary school teacher, so perhaps it was to do with their profession. Hugh and Elisabeth brought a ten year old boy, Richard, with them who we think was Hugh’s younger brother. On arrival the newly-weds lived in various different houses before moving into Llys Silin, a house near the school where they settled into married life and quickly became part of the community. Richard was enrolled at the school and Hugh started to find his feet as Head Teacher. The previous master, Mr Hayley, had been ill off and on, including seven weeks suffering from typhoid when the school had to be closed, and consequently the Inspector’s report, although commenting on the improved spelling and discipline, found that the school was dirty and that the curriculum was wanting. Soon after Mr Hayley returned from his illness the weather closed in and due to heavy snow and icy conditions the school was closed again. It was the last straw and Mr Hayley tendered his resignation. Hugh had work to do. He improved the curriculum, adding practical skills to the usual academic lessons. These were the children of farmers and agricultural labourers and for the boys, carpentry and gardening were useful attributes and sewing and housewifery set the girls up for their own domestic life. He introduced paper modelling and drawing and, closer to his heart, he started a school choir. Student numbers varied between fifty and hundred every year so the school employed one or two Pupil Teachers and Mrs Williams helped out when she could. Pupil teachers at that time were older students who, for a few pounds a year, rather like Jane Eyre, worked as assistant teachers until they were eighteen so that if, passing the required examination, they could get the chance to go to a training college and become certificated. Mr Williams wasn’t a certificated teacher but always encouraged his assistants to be so. At home, Elisabeth was having a baby almost every year, and by the time the century turned she had given birth to eleven children, seven boys and four girls. Three of them died when still babies, Robert, living for only five weeks, Mary Louise for four months and Thomas Cecil for only a few days. Twins, Margaret and Lucy, are recorded as being baptised, probably in August 1900 but there is no record of them having survived. But the other children thrived and it must have been a full and noisy household for Hugh to come home to after school. Sadly, a few days after the twins were baptised, Elisabeth died suddenly, possibly as a result of childbirth and Hugh and the children were left without her. It came as a terrible blow but he had the sympathy of the entire village who turned out for Elisabeth’s funeral in great numbers. Looking after the children must have been difficult especially as all the three older ones were boys, Isaac, 15, Alfred,14, and John 12. The oldest girl, Elizabeth, was only eleven and then there was William, 10, David,7, Hugh, 6, Gwladys,4 and Thomas, 3 as well as the twin babies. After a year and in desperation, Hugh turned for help to his sister-in-law, Margaret Thomas. On the 1901 census in her village in Carmarthenshire she was described as a widow and a pauper with four children living at home. The oldest child, John, 19, was an elementary school teacher so he was bringing in some money. Elizabeth, 15, was described as a drapery apprentice and Jane, 10, was a scholar, but Annie, 13, wasn’t at home. Perhaps she was in service. In 1902 Hugh travelled down to Carmarthen and married Margaret at the same church where thirty years earlier he’d married her sister. It was not until 1907 that the Marriage Act was amended to allow a marriage to a sister-in-law, but Hugh obtained permission from the church and the two families were combined first at Lys Silin and then at Oakdene. Settled now, Hugh concentrated on his school duties. The school log books record the daily attendance and importantly of the weather. This was a farming community, where the children walked to school, sometimes several miles and if there was a storm, then the boys and girls from outlying farms wouldn’t attend. Sometimes there was a lack of coal to heat the school so the children had to be sent home. He also recorded the epidemics of measles and chicken pox, which sometimes would close the school and the election days, sports days and other community activities that would require the school hall. The children had a week’s holiday at Christmas, another week at Easter and three weeks in the summer. Mr Williams was not happy when they took extra days off to help on the farms and tried a tactic of giving a half holiday to children who recorded a good attendance but it didn’t really work and he was angry when school was skipped in order to gather wymberries on the Gyrn , harvested for dye making in Lancashire. During World War 1 the government recognising that the men were away from home, allowed the elder children weeks off to help bring in the hay and the harvest. The Inspectors came to the school regularly and gave reports on how the children were performing at their lessons and the condition of the building. Mr Williams recorded their inspection carefully, ‘discipline is kind but should be firmer,’ said one report in 1908 and in 1913 ‘a good wall map is used in the geography of Europe but at the same time their knowledge of England and Wales is meagre.’ Music at the school, a particular love of Hugh was praised throughout the years. John Thomas, his nephew, was a pupil teacher at the school but soon he went away to train and get his teaching certificates but he was followed at the school by his sisters, Annie and Bessie (Elizabeth) both taking up teaching duties. Occasionally Mrs Williams would come in to give lessons, so in many ways it was a family business. Of his own children, Isaac left Llansilin and went to Yorkshire where he worked for the railway. Alfred, John, William and David emigrated to New Zealand. David enlisted in the New Zealand Rifle Brigade and was killed in September 1916. The others stayed in the village or close by. Mr Williams not only trained the school choir but the church choir who entered local eisteddfods. He started a brass band, He was an Oddfellow, a friendly society, being secretary to the Glyndwr Lodge. As stated earlier, he was the local registrar, Parish secretary, and an official at the Cattle show, and sheepdog trials. He retired from the school in 1923 having served for forty two years. In that time the school had changed out of all recognition, not only in the improved building but with more subjects being taught, and more interesting activities to be had. The children were well prepared for their adult lives. Leaving must have been a wrench but he and his old friends in the village met regularly at a bench at the top of the village where they would set the world to right. They were known as the Llansilin Parliament! Hugh Williams lived for nine years after retiring and died in 1932 at the age of seventy four. His funeral at the parish church was hugely attended, not only by his large family and many friends but by people from near and far, some of them ex pupils and others who recognised the contribution this man had made to his community. The service was fully choral and the vicar in his address paid a glowing tribute to the life-long services rendered by the deceased. Hugh Solomon Williams, born in a poor quarry village, who managed to educate himself and become a teacher and much more, ended up respected and remembered by a whole and grateful community.

Katherine Rosenberg

Most of the research for this article was done by Mary Morris who compiled the School Log Books, searched the burial records and spoke to residents of Llansilin.

Schooling in the Llansilin Area by Harry Ruckley